In the mid-‘50s, Raleigh was still a radio town and WPTF was the powerhouse station. CBC was on the air with WRAL-AM and FM. The next frontier was television, and the battle was about to begin.

Once again we turn to a chapter in Fred Fletcher’s book, “Tempus Fugit,” (published in 1990) for an inside look of how it all went down. Let’s get ready to rumble.

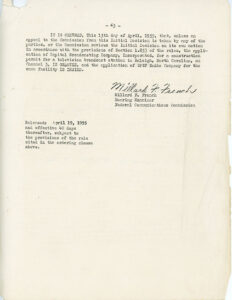

A photo of part of a document showing the initial grant of TV5 license by the FCC. (Click photo for larger view)

A photo of part of a document showing the initial grant of TV5 license by the FCC. (Click photo for larger view)

Chapter 16. Radio with Pictures

It seems that when circumstances become comfortable something has to come along to stir them up again. By the early ‘50s WRAL had become a substantial radio property. We had the AM and FM frequencies; we anchored the Tobacco Network; and we had respectable audiences for our sports programming. Then, along came television.

Actually, television had been around for years. When A.J., mother and I went to the World’s Fair in Chicago in 1934 after I graduated from George Williams College, we visited the RCA exhibit, and I think I was on television for the first time. Then in 1939, I read where some people at CBS had broadcast one of Columbia University’s baseball games. But it wasn’t until the early ‘50s that television became a factor in the Raleigh market. A license was granted to WTVD in Durham, and people in the Raleigh-Durham area began to buy television sets.

I remember Dick Mason calling me one day and asking what we were going to do about “this television thing.” I told him I didn’t know. Television was for people with a lot of money, and looking at the resources we had with the radio stations, we didn’t have that kind of money. At that moment, I probably thought that we would stick to radio and let somebody else have the television.

That’s not, however, the way it worked.

To give credit where it is due, WPTF had done a lot of preliminary work to get a VHF channel assigned to the Raleigh area. This is the first step in the long process of gaining the FCC’s permission to broadcast over the public’s airwaves. However, this first step simply sets aside a frequency that will be awarded in a particular area. If more than one applicant wants it, a hearing judge decides who gets it.

A.J. decided that we would compete with WPTF for it. This represented a real commitment of money and time, because we not only had to spend time at the hearings – nine weeks as it turned out – but we had to spend at least that much time preparing for them, doing research, gathering affidavits, and putting together exhibits.

And suddenly we were back to the David and Goliath relationship with WPTF.

With the exception of the work being done by our Washington attorneys (my brother, Frank, and his firm), we did most of the research and writing ourselves while we did our regular jobs at the station. The finished presentation was fourteen large volumes, tracing the history of Capitol Broadcasting, WRAL, and the Tobacco Radio Network, and outlining the proposed television programming. We had charts and graphs and words – a lot of words. Much of the presentation of WRAL Radio had to do with Tempus Fugit, our sports coverage, and our community activities.

(The words were mostly written by a young man named Scott Summers, who had been hired to help put the presentation together. Scott, a newsman, would write the copy and we would send it up to our Washington lawyers for approval. Inevitably, Scott’s copy would come back sprinkled with commas when he, with a lot of muttering and fuming, would put in the final draft. We didn’t realize the depth of his frustration until Vincent Welch, our co-counsel, came to Raleigh for a meeting. Sometime during the day we had the opportunity to introduce Welch to Scott. On finding out who our guest was, Scott stuck out his hand and jaw and said, “Pleased to meet you, you comma-loving SOB.” Then he turned and went back to his writing.

WPTF, on the other hand, had hired some specialists to help them put their presentation together. We heard, in a roundabout way, that at least one of their specialists would be glad to let us know what was going on in the WPTF camp. We said, “No, thank you.” We had just as soon not know.

The hearing was convened in April of 1954. The WPTF delegation was rather nicely situated at the Willard Hotel in downtown Washington. The WRAL group was comfortably, but not so elegantly, installed at the Hunter Lodge Motel, about 13 miles south of Washington.

A.J. and I shared a room, and he complained about my snoring. There was, I suppose, some justice in that, since he used to scare me silly in the middle of the night when he rattled the walls with his snores. We managed to accommodate each other since we wanted to save the price of the room.

Food wasn’t a problem, since we were so nervous that we couldn’t eat much anyway. I lived for most of those nine weeks on Cream of Wheat and poached eggs. I’m not sure that my stomach would have handled anything more substantial.

It was obvious from the start that WPTF was taking our challenge seriously. When we had applied for the radio license, they had made a half-hearted effort to convince the FCC that one station was enough for a market the size of Raleigh, but it didn’t seem to bother them that we were granted a license. This was different.

Like WRAL, WPTF had a Washington firm that usually represented their interests before the FCC. However, they decided that for this hearing they needed bigger guns. In addition to their usual firm, they retained General Kenneth Royall. Royall was well known around Washington, not only for his legal work, but as Secretary of War under President Eisenhower. From the very beginning it looked like Royall wanted to give the WPTF group their money’s worth. We didn’t even get to the hearing before he started acting like a general.

The first instance was in a pre-hearing meeting with the examiner. The hearing examiner, envisioning a long and involved procedure, asked the opponents to stipulate certain facts that he considered obvious. One of these was the financial ability of both parties to properly operate a television station if awarded the license. We readily agreed. The general didn’t. “Nobody is going to tell me how to try my case,” he said.

My brother, Frank, who was, as I’ve mentioned, our Washington attorney, wasn’t intimidated by the General. He smiled and noted that the General’s statement was “spoken like a true general.” It was, I suppose, an innocent enough statement, but General Royall felt called upon to explain to us all that he had been that way even before he became a general. Which was, Frank observed, probably how he became a general.

Later in the hearing Royall gave us another bit of his philosophy when he told the examiner that he “would agree with nothing that he had not first proposed.” So much for friendly competition and cooperation. It’s just as well, because it wouldn’t have lasted long once the hearing got underway.

An FCC hearing is one part fact, as presented in the hearing documents, one part defending those facts, and one part shooting down the other side’s facts. Those parts are not necessarily equal. Actually, once the hearing starts, the facts themselves seem to be no more than a background for the lawyer’s maneuvers.

Our lawyers, for instance, learned that the examiner was a second lieutenant in the war. They assumed that, as a civilian caught up in the military in war time, he might have some residual resentments about the officers over him – and when you are a second lieutenant, all the officers are over you. So the lawyers told us we should refer to Kenneth Royall as “General Royall.” For nine weeks we never let anyone forget that General Royall was a general.

One of their strategies seemed to be to make me look dumb. Scott had written in a part of the presentation that “gathering news in the local market was not a matter of legerdemain.” Someone at the WPTF table suggested to General Royall that he ask me to explain what that meant, expecting, I suppose, to trip me up on “legerdemain.” What they evidently didn’t know was there was nobody in Raleigh who was more aware of manpower, sweat and planning that went into a good news operation. I had been working on it for years and could assure them that it wasn’t magic; it was hard work.

Then General Royall asked me if it were true that I had broadcast the location of speed traps on Tempus Fugit. I acknowledged that I had at every opportunity. He was making a big issue of this characteristic of lawlessness when the hearing examiner muttered that it sounded like a good idea to him. They dropped that point.

They also jumped on me about WRAL carrying beer advertising. At that time, WPTF did not. That point sailed out the window too when someone brought the examiner a package wrapped in brown paper. Someone, evidently hoping to be funny, asked the examiner if that was his booze. He smiled and said that he wished it were, but unfortunately it was his laundry. It was obvious they were not going to make a lot of points with our beer advertising.

Things seemed to be going well for us; so well, in fact, that I became comfortable on the witness stand. I had started out sitting straight up, almost at attention. By now, I was in about the same posture I use to watch television at home. Every time they charged me, it seemed that the facts and the examiner were on my side. And that was, so far as I was concerned, exactly the way it should be.

One of our attorneys, Vinnie Welch, disagreed. We were walking out to the hall one afternoon when he pushed me around the corner, grabbed my jacket, and stuck his face right in my face. “Listen, you SOB,” he said. “When you get back in there, you look scared. You sit right on the front of your seat. You take your time to answer the questions. And you look scared.”

When we went back in, I did just as I was told. General Royall and the opposition didn’t scare me that much, but I had a healthy regard for what my own lawyer might do to me.

For nine weeks, it was a day and night operation. We would be in the hearing room all day; then we would return to the lawyers’ office and work on the next day’s testimony. Literally thousands of man hours were expended on attacking and defending the most minute of points.

When the examiner rendered his opinion, and the TV grant was awarded to WRAL in 1956, the decision was based on two things: what the examiner called a reasonable distribution of media and the integration of ownership and management. That simply meant that, since we had a 250 watt station and WPTF had 50,000 watt station, we would be more equal if we were awarded the TV grant, and that at WRAL, the owners and the managers were one and the same. WPTF was (and is) owned by Durham Life, and the owners would have no real part in managing the station.

It was as simple as that.

And as complicated and exhausting as that.

But it put us into television. Seventeen years after going into radio, I had a new career.

Thanks to Corp’s Pam Allen for this capcom story. Pam Parris Allen is a former WRAL newscast producer/director who now works as a researcher and producer on the CBC History Project.